Distributed consensus is a fundamental concept in computer science and distributed systems. It refers to the process by which a group of nodes or participants in a distributed network reach an agreement or consensus on a particular piece of information or a decision, despite potential failures, delays, or faults in the network.

Traditional consensus algorithms, as those seen in distributed databases, typically rely on the assumption that the group of participating nodes is predetermined and unchanging. In other words, it is assumed that a previous configuration process, whether manual or automatic, has established a specific and authenticated set of participants who can mutually authenticate themselves as members of this group. As a result, these consensus algorithms do not need to take into account the possibility of failures that occur as a result of the malicious actions of an adversary participating in the consensus algorithm.

This category of failure that a process can experience is called a Byzantine failure. Byzantine failures are failures without any restrictions. They can occur due to various factors, including malicious actions by an adversary. In the case of a Byzantine failure, a process may send contradictory or conflicting data to other processes, or it might go dormant and then reactivate after a prolonged delay. Between the various types of failures that can occur, Byzantine failures are significantly more disruptive. Hence, a consensus algorithm designed to handle Byzantine failures must demonstrate resilience against any conceivable error that might arise.

The problem of achieving consensus in a decentralized environment, peer-to-peer network, is particularly relevant in the context of distributed ledger systems, such as blockchain systems, where multiple participants must reach consensus on the global state of the system, even in the presence of malicious participants. Therefore, blockchain systems must find a way to solve the Byzantine Generals Problem. So how does a blockchain system, such as Bitcoin, solve the Byzantine Generals Problem?

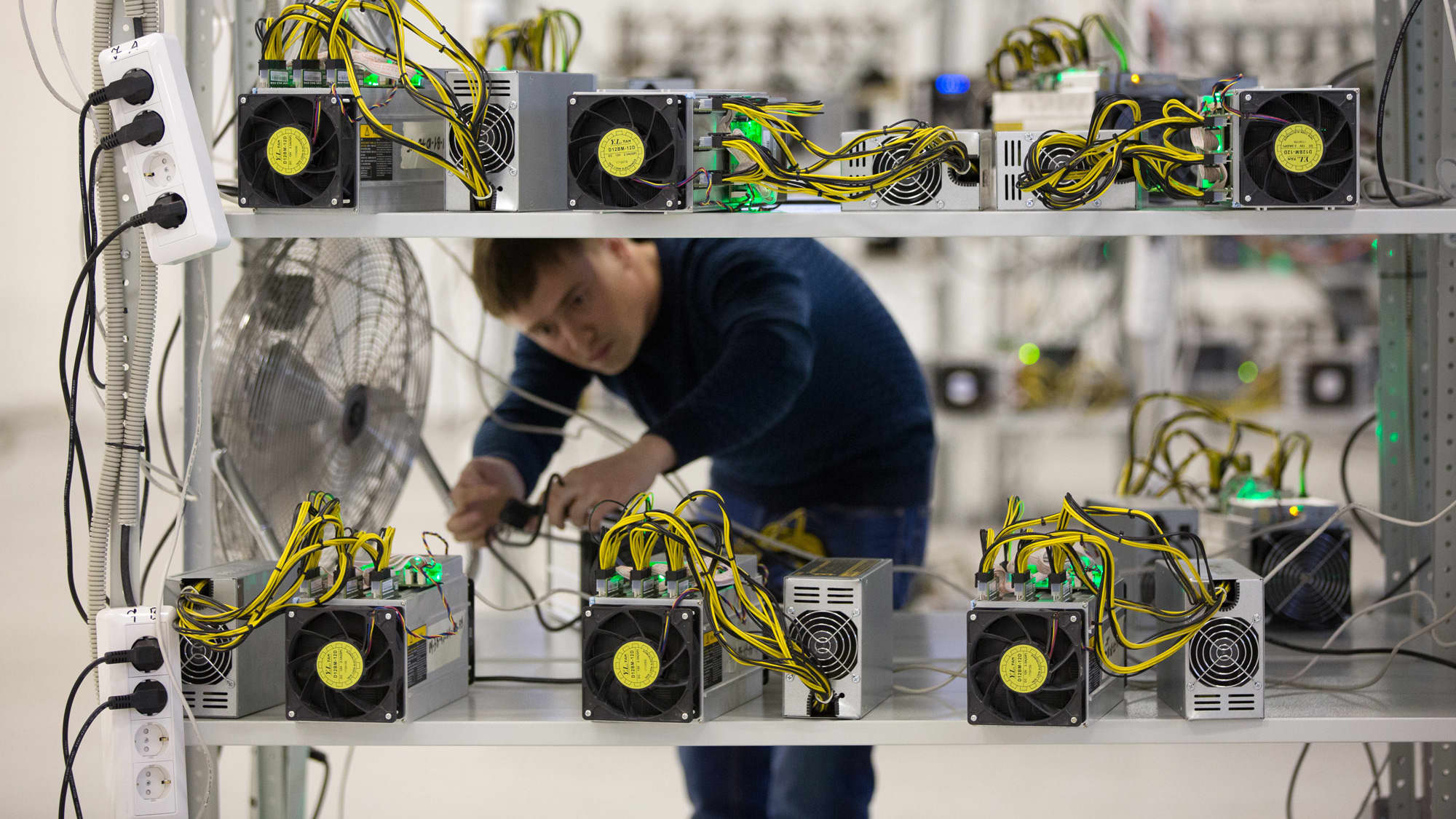

Proof-of-work is the consensus algorithm that many blockchain systems, such as Bitcoin, use to reach consensus and avoid byzantine faults. The fundamental concept behind proof-of-work involves the idea of choosing nodes based on a resource that is allocated in a manner that aims to prevent any single entity from dominating it, such as computing power. In other words, a node in the network decides what the next block will be based on the amount of work it has done. This will later be propagated across the network for other participants to verify and include in their own state of the blockchain.

Proof-of-work is thus achieved by showing the work done to solve a hash puzzle. This hash puzzle, depending in its difficulty, requires extensive computing power. To form a block, the proposing node must discover a nonce, a unique number. When this nonce is concatenated with the previous hash and the list of transactions within the block, and the hash of this combined string is computed, the resulting hash should be a value within a relatively small target range compared to the overall range of possible hash values. This target range is defined as values falling below a specific threshold, which dictates the difficulty of the hash puzzle.

Here is pseudocode for the proof-of-work algorithm:

After the computing power has been dedicated to ensuring the satisfaction of the proof-of-work, altering the block becomes a hard task, requiring the entire process to be redone. As subsequent blocks are linked to it, any attempts to modify the block would necessitate the repetition of work for all the blocks that follow. The proof-of-work mechanism also addresses the issue of determining representation in majority decision-making. If a majority were determined based on a one-IP-address-one-vote system, it could be vulnerable to manipulation by individuals who can allocate numerous IP addresses. In contrast, proof-of-work essentially establishes a one-CPU-one-vote model. The majority decision is symbolized by the longest chain, which reflects the most substantial effort in terms of proof-of-work. If the majority of computing power is under the control of honest nodes, the honest chain will experience the most rapid growth, outpacing any competing chains. To alter a previous block, an attacker would need to redo the proof-of-work for that block and all subsequent blocks, in addition to surpassing the cumulative work of the honest nodes. The likelihood of a slower attacker catching up diminishes exponentially as more blocks are added.

To adapt to evolving hardware capabilities and changing interest in running nodes, the difficulty of the proof-of-work is adjusted using a moving average that targets an average number of blocks generated per a given time interval. If blocks are being generated too quickly, the difficulty level increases accordingly.

Essentially, proof-of-work based blockchain systems incorporates the concept of randomness. Furthermore, it dispenses with the idea of a fixed start and end point for achieving consensus; thus it can be claimed that proof-of-work does not solve the Byzatine Generals Problem as intended. Instead, consensus is established over an extended period of time. Even at the conclusion of this timeframe, nodes cannot be certain that a specific transaction or block has been included in the ledger. Rather, over time, the likelihood of your perspective aligning with the eventual consensus increases, while the probability of diverging viewpoints decreases exponentially. These distinctions in the model are fundamental to how proof-of-work navigates around the traditional challenges posed by distributed consensus protocols.

It is also very important to realize that incentives play a crucial role in promoting the honesty of nodes within the network. If a self-interested attacker manages to accumulate greater computing power than all the honest nodes combined, they face a strategic decision. They must decide whether to exploit this power for malicious purposes, such as reclaiming their own payments through fraudulent means, or to employ it for the creation of new coins. It should be economically more advantageous for the attacker to adhere to the established rules, which, in their favor, result in a larger share of newly generated coins than the cumulative share of everyone else. This approach of following the rules rather than subverting the system safeguards the integrity of the attacker’s own wealth and ensures a more profitable outcome. Therefore, the proof-of-work algorithm does not safeguard against hacks but only minimizes the chance of their occurrence by creating greater financial incentives for network participants to comply with the rules of the system than to break them.

Thus one can say that proof-of-work solves the Byzantine Generals Problem, as it achieves a majority agreement without any central authority, in spite of the presence of malicious participants and despite the network not being instantaneous. But the key part to realize is that it reaches consensus eventually. Therfore, according to distributed systems terminology, a blockchain system using proof-of-work as its consensus algorithm can be categorized as having the property of eventual consistency. Meaning, it will reach consensus even when faced with faulty or malicious participants and communication paths, but over a given amount of time.

References

- Nakamoto, S. (2008) Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf

- Narayanan, A. et al. (2016) Bitcoin and cryptocurrency technologies: A comprehensive introduction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Antonopoulos, A. (2024) Mastering bitcoin: Programming the open blockchain. S.l.: O’Reilly Media.