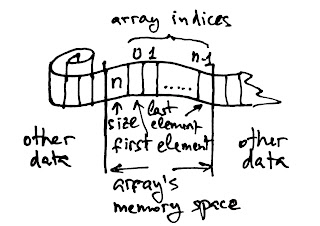

In Go, arrays and slices share a close relationship, with slices acting as

lightweight linear data structures that provide access to subsequences or

even the entire slice of elements within an array. The underlying array

associated with a slice serves as its foundation. A slice is composed of

three crucial components: a pointer, a length, and a capacity. The pointer

directs to the first element accessible through the slice, which may not

necessarily be the initial element of the underlying array. The length represents

the number of elements within the slice, while the capacity, typically

determined by the number of elements between the slice’s start and the end

of the underlying array, imposes an upper limit on the length. These values

can be obtained using the built-in functions len and cap.

In order to show this concept better, let’s say we declare and intialize an array that represents the days of the week.

days := [...]string{1: "Monday", /* ... */ 7: "Sunday"}

fmt.Printf("%T\n", days) // [8]string

Notice, that the array element at index 0 would contain the first value, but because days are numbered from 1, we can leave it out of the declaration and it will be initialized to the empty string. So Monday is

days[1]and sunday isdays[7].

Now, say we define two slices for the work week and the weekend:

work := days[1:6]

fmt.Println(work) // [Monday, ..., Friday]

fmt.Printf("%T\n", work) // []string

weekend := days[6:8]

fmt.Println(weekend) // [Saturday, Sunday]

fmt.Printf("%T\n", weekend) // []string

The slice operator s[i:j], where 0 <= i <= j <= cap(s), creates a new slice

that refers to elements from index i up to, but not including, index j

in the slice s. The slice s can be an array variable, a pointer

to an array, or another slice. In our case it is an array. The resulting slice

will have j - i elements. If i is omitted, it defaults to 0, and if j

is omitted, it defaults to the length of s.

The length and capacity of each of the slices in respect to the underlying array,

in this case days can be depicted as follows:

Now, there are two key considerations that we need to keep in mind. The first one

being that if we slice beyond cap(s) it will cause a panic, but slicing beyond

len(s) extends the slice.

fmt.Println(days[:15]) // panic: out of range

The second consideration is that a slice contains a pointer to an element of an array. Therefore, passing a slice to a function allows the given function to modify the underlying array elements. This is often desirable but one must be aware of it. In the contrary, passing only an array will create a local copy of the array and not modify the underlying elements in-place.

// reverses a slice of ints in place

func reverse(s []int) { /* ... */ }

a := [...]int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4}

reverse(a[:]) // slice of the entire array

fmt.Println(a) // [4, 3, 2, 1, 0]

Finally, in order to fully understand how slices work, one must understand how

the built-in append function works. The append function appends elements to

slices. For instance, consider a version called appendInt

that is used for []int slices:

func appendInt(x []int, y int) []int {

var z []int

zlen := len(x) + 1

if zlen <= cap(x) {

// there is room to grow, extend the slice

z = x[:zlen]

} else {

// there is not enough space, allocate a new array

// grow by doubling, for amortized linear complexity

zcap := zlen

if zcap < 2 * len(x) {

zcap = 2 * len(x)

}

z = make([]int, zlen, zcap)

copy(z, x)

}

z[len(x)] = y

return z

}

Every call to the appendInt function needs to verify if the slice has enough

capacity to accommodate the new elements within the existing array.

If there is sufficient capacity, it extends the slice by creating a larger

slice within the original array, copies the elements into the new space,

and returns the updated slice. Both the input x and the resulting z

share the same underlying array.

However, if there is insufficient space for growth, appendInt must allocate

a new array that is large enough to hold the desired result. It then copies

the values from x into the new array and appends the new element y.

As a result, the slice z now refers to a different underlying array than

the array x refers to.

For efficiency, the new array allocated by appendInt is typically larger

than the minimum size required to hold x and y. By expanding the array

by doubling its size during each expansion, excessive allocations are avoided,

and appending a single element takes constant time on average.

The program provided serves as a demonstration of this efficiency.

func main() {

var x []int

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

x = appendInt(x, i)

fmt.Printf("%d cap=%d\t%v\n", i, cap(x), x)

}

}

Each change in capacity indicates an allocation and a copy:

0 cap=1 [0]

1 cap=2 [0 1]

2 cap=4 [0 1 2]

3 cap=4 [0 1 2 3]

4 cap=8 [0 1 2 3 4]

5 cap=8 [0 1 2 3 4 5]

6 cap=8 [0 1 2 3 4 5 6]

7 cap=8 [0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7]

8 cap=16 [0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8]

9 cap=16 [0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]

The built-in

appendfunction employs a more sophisticated growth strategy compared to the simplistic approach used byappendInt. In general, we cannot predict if a particularappendcall will trigger a reallocation. Therefore, we cannot assume that the original slice and the resulting slice will refer to the same underlying array or to different arrays. We also cannot assume whether operations on elements of the old slice will affect the new slice or not. Consequently, it is common practice to assign the result of anappendcall back to the same slice variable that was passed as an argument.

References

- Donovan, A.A.A. and Kernighan, B.W. (2020) The go programming language. New York, N.Y: Addison-Wesley.